By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com; June 27, 2019)

The news media generally likes simple narratives. It makes their job easier and makes the news more digestible for consumers.

And while there is no shame in making one’s job less complicated or work product more consumable, it can easily misrepresent reality.

The latest example is from the 2020 Democratic nomination race and the simplified narrative goes something like this: Since offering more practical and concrete progressive policy proposals, Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren is challenging Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders for the hearts and minds of progressive Democrats.

The simplifying assumption is that Sanders and Warren are fighting for the same progressive voters. But is that true?

Of course, on a reductive level, this narrative is true by definition. All Democratic candidates are competing for the same voters in the Party’s base. But as documented in an earlier analysis of the December 2018 American National Election Study (ANES), Warren’s core supporters are demographically and attitudinally different from Sanders’ core supporters. Contrary to the media storylines, Warren’s support has always been concentrated among the most elite segments of the Democratic Party. She is slowly rebuilding Hillary Clinton’s 2016 coalition: highly-educated, upwardly mobile, urban/suburban women (and the men that love them).

In the December 2018 ANES, Warren supporters were significantly more likely to be older, upper-middle-class, educated, white females in comparison to Sanders supporters. Likewise, attitudinally, Warren supporters were more centrist in their views. Warren, the candidate, might be progressive on bank reform or student debt forgiveness, but her core supporters were more aligned with the Third Way Clintonians than the Berniecrats.

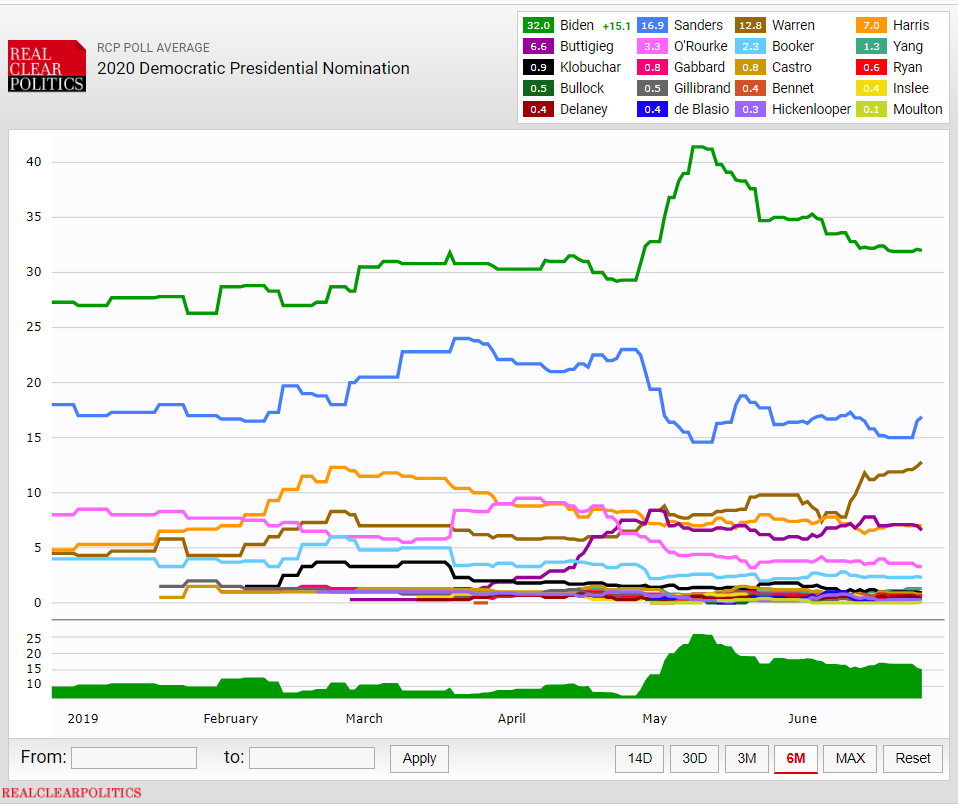

Further underwriting the Warren versus Sanders narrative is Warren’s recent rise in the polls among likely Democratic primary voters (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: RealClearPolitics.com Poll Averages for the 2020 Democratic Presidential Nomination Candidates

Warren’s poll numbers (the brown line) have risen consistently since early May, reaching a high of 13 percent in the latest RealClearPolitics.com poll average, while support for Sanders (the blue line) has remained relatively constant at around 17 percent. Warren most certainly is taking some potential supporters from Sanders, but do they really share the same ‘progressive’ voter base?

Well, it depends.

It is just as likely Warren is gaining support from former supporters of other candidates who have seen their support slacken recently — candidates like Beto O’Rourke and Cory Booker. Indeed, as we see in the aggregate data, Warren’s rise is coming at the expense of those two candidates and with little relationship to changes in Sanders support.

But the Warren versus Sanders narrative is stronger than ever.

“By running a campaign heavy on both policy and biographical details, she has wrested some high-profile liberal supporters away from Mr. Sanders, and in some polls, has shown signs of ticking upward,” writes New York Timesreporters Astead W. Herndon and Sydney Ember. “But while Ms. Warren has gained ground, she has not yet cast a shadow of her own. Mr. Sanders still holds a large advantage in the polls — a point his advisers eagerly highlight — and his supporters say he remains the clear progressive standard-bearer among the larger electorate.”

“They both have a crusader mentality around correcting what is wrong,” says Washington Rep. Pramila Jayapal, a prominent member of the House Democratic Progressive Caucus. “They understand they are speaking to a similar vision of the country, and obviously they are trying to distinguish themselves from each other.”

“The challenge for both candidates is that, since they’re appealing to many of the same voters, any critiques must be handled delicately to avoid alienating possible backers,” writes Washington Post political reporter Sean Sullivan.

These largely data-free conclusions are plausible, but when we look at changes over time in aggregate support for each candidate it is evident that many of these media-driven storylines are more assumption than fact.

Allies and Antagonists

The tactical relationships between the candidates emerge when their support is viewed in the aggregate over time (see Figure 1). Across the major candidates (i.e., polling over 5 percent consistently), some candidates rise and fall together (allies) and some rise at the expense of other candidates (antagonists). And, of course, those relationships can — and do — change over time.

For example, starting in late April, around the time of Biden’s entrance into the race, Biden and Sanders became clear antagonists — as Biden rises, Sanders falls. Some of those Sanders supporters certainly went to Warren, some to Biden, and probably a few went to the other candidates. It is hard to know without individual-level panel data.

But aggregate data has a nice characteristic: it tends to cancel the noise inherent at the individual-level. Yes, we do care about who is going where with their support. If Sanders is losing support among women, his team needs to know that. But, in the aggregate, the inter-candidate dynamics become observable.

Using RealClearPolitics.com’s polling database (containing 69 separate national surveys since October 2018), we can see which candidates move together in aggregate support (allies) and which move in opposite directions (antagonists).

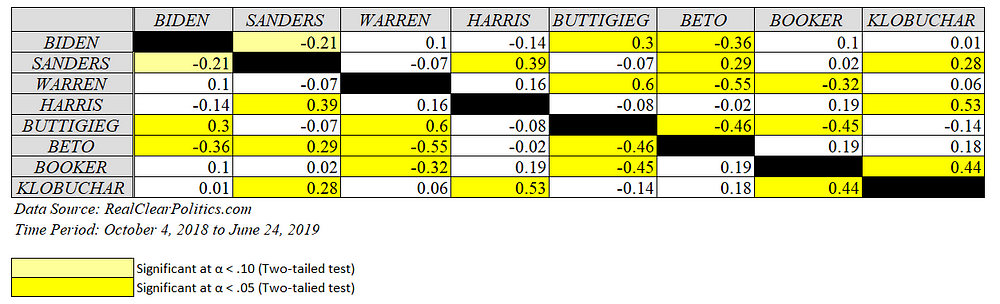

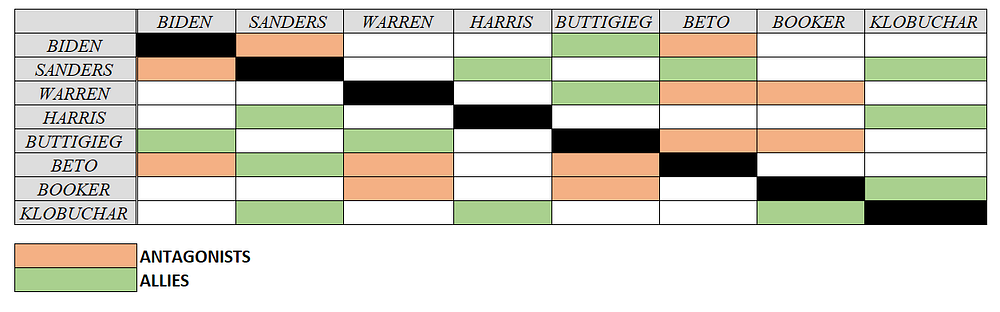

Figure 2 shows the bivariate correlations among the top-tier Democratic candidates over the period from October 2018 to mid-June 2019. The relationship of most interest — Warren and Sanders — indicates no obvious relationship. Sanders support levels do not change in concert with Warren’s over this period.

That is not the case between Biden and Sanders, where, if one goes up, the other goes down. While not a strong statistical relationship, it has grown stronger since Biden’s official announcement.

Conversely, Sanders’ aggregate support moves in tandem with Kamala Harris, Beto O’Rourke, and Amy Klobuchar — three candidates most often associated with corporate-friendly centrism. Up to this point in the race, at least, growing support for centrist candidates not named Biden helps the Sanders campaign.

Tactically, as a candidate, that is good information to know.

Figure 2: Correlations of Democratic Candidate Support in the 2020 Democratic Nomination Race

Figure 3 simply summarizes the Figure 2 correlations by assigning the antagonist and allies labels to each candidate pair. Such that, Biden and Sanders are antagonists. As one goes up, the other goes down. The same is true for Biden-Beto, Warren-Beto, Warren-Booker, Buttigieg-Beto, and Buttigieg-Booker.

Besides the Sanders allies described previously, the other allied pairs include: Biden-Buttigieg, Warren-Buttigieg, Harris-Klobuchar, and Booker-Klobuchar.

Figure 3: Allies & Antagonists in the 2020 Democratic Nomination Race (Oct. 2018 to June 2019)

All of these pairings could change overnight. As of now it appears, Harris, Beto and Klobuchar rise jointly with Sanders. Likewise, Buttigieg’s fortunes seem tied to Warren and Biden.

But as candidates drop out, these dynamics can change instantly. In the end, should it come down to just two candidates — which nomination races normally do — the last two standing will most certainly be an antagonist pair.

Correlation is not Causation

The correlations in Figure 2 are not, of course, evidence of causation. Biden’s rise in the polls does not cause Buttigieg’s support to rise. It may. But we can’t say that from the looking at contemporaneous correlations.

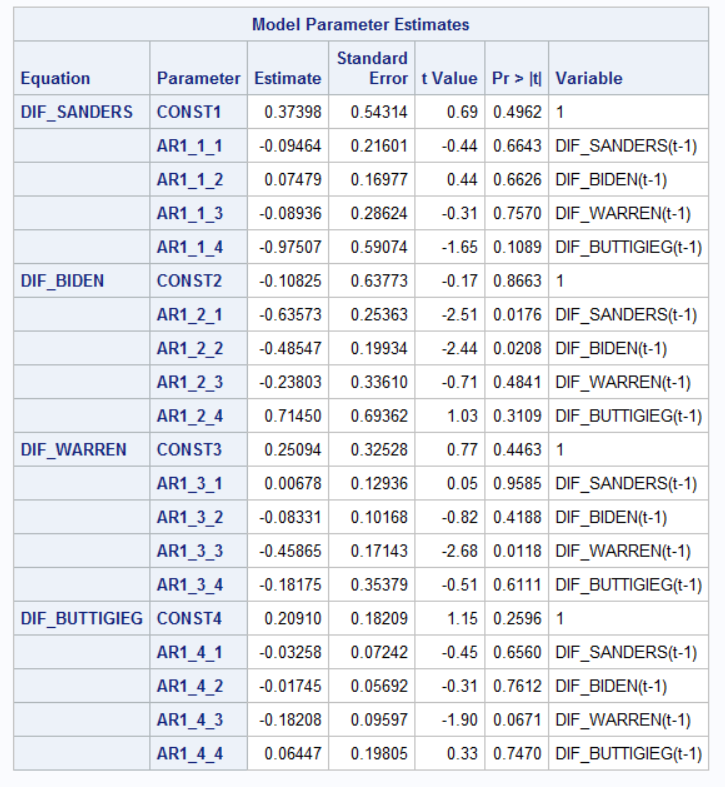

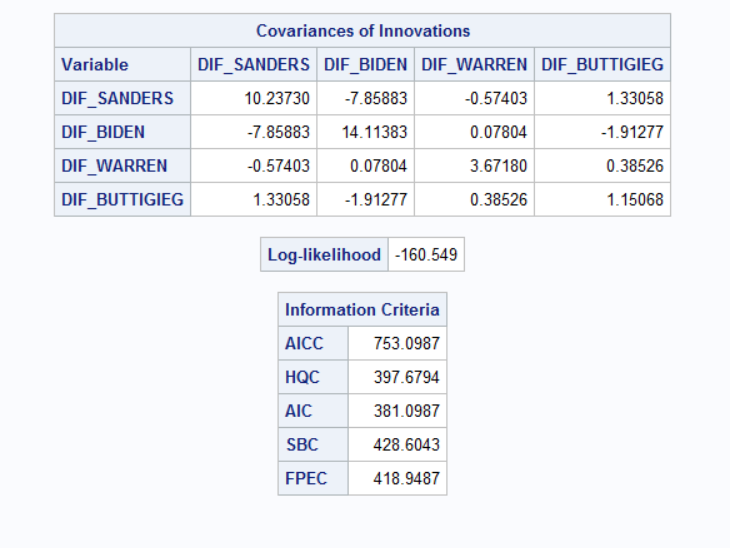

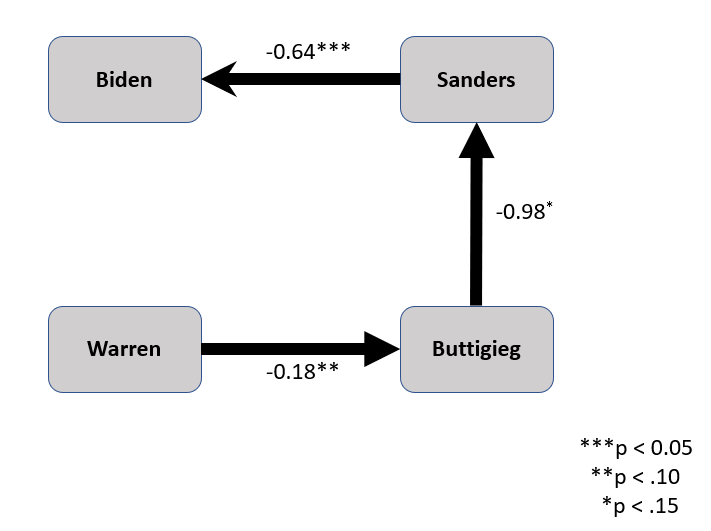

For a little extracurricular exercise, I generated a *very exploratory* vector autoregressive model (VAR) of candidate support using the weekly time-series data for the top four candidates (see Figure 4). Given the small sample size (n = 37 weeks), I cannot draw any strong conclusions; but, it is fun to conjecture when there is a little bit of data behind it — no matter how sketchy.

Figure 4: A Causal Model of Democratic Candidate Support in the 2020 Democratic Nomination Race

With the small sample size caveat in mind, the estimated VAR model shows evidence of a causal system in which a rise in Warren’s support depresses Buttigieg’s support… which helps Sanders…which hurts Biden. In other words, if this causal model is correct, Warren’s rise up to now may be helping Sanders by moderating Buttigieg’s rise, which comes at Sanders’ expense, according to the VAR model. If true, the Sanders campaign may need Warren to stay in the race at least until Buttigieg drops out.

Last thoughts

The biggest mistake we often make is the assumption that voters choose candidates based on the issues. Yes, issues matter. But, often, only indirectly. There are many vote decision paths and, as research as shown, voters often adjust their policy views after they pick a favorite candidate or party.

Warren may be a genuine progressive — closer to Sanders than Biden in her policy views — but her supporters are not necessarily as progressive. Many are the same centrists that lined up in 2016 for Clinton over Sanders.

Over the next year, as candidates drop out of the race, we may see a 2016 redux with Warren and Sanders the last candidates standing, battling for the soul of the Democratic Party.

The lazy conclusion would call that outcome a victory for the Democrats’ progressive wing, but more likely it is merely the reformation of the same 2016 alliances: Centrist (corporatist) Democrats behind Warren versus the Berniecrat progressives.

That is not as exciting an interpretation, perhaps, but probably the more accurate one.

- K.R.K.

Vector Autoregression Model Output (SAS)

The data source is RealClearPolitics.com’s polling averages for the top four Democratic candidates since October 2018. The data series for each candidate was differenced in order to make it stationary. In total, there were 37 weeks of data. All data and SAS computer code is available upon request (kroeger98@yahoo.com).