By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com, April 28, 2018)

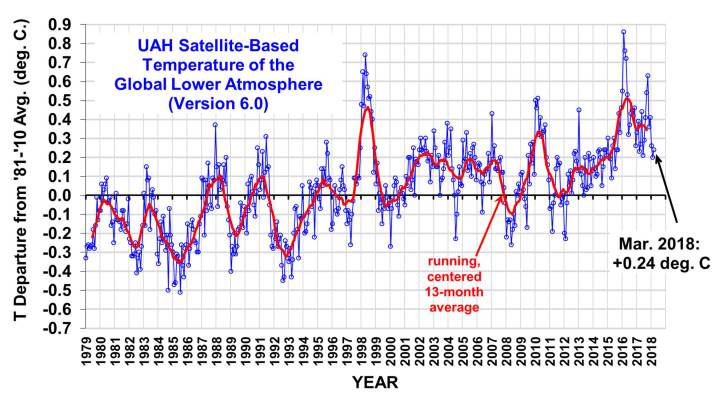

No serious person can deny that global temperatures are warming (see chart below) and mankind is a major cause of this geologically recent trend.

Nonetheless, a real scientific debate continues in the climate science community regarding exactly how fast the globe is warming and exactly what is humankind’s contribution to that warming relative to natural variation. And with respect to the higher order impacts of global warming, such as rising sea levels, heat waves and tropical storm intensities, there is even more uncertainty, though most climate scientists agree sea levels will rise, heat waves will be more frequent, and tropical storms will be more intense, on average.

On one side of the debate is the vast majority of climate scientists who argue we will see global temperatures increase by at least 3.0°C over pre-industrial levels by 2100 with catastrophic results to the environment. I refer to them as climate alarmists as the term conveys the urgency they feel about the importance of converting the world economy to renewable energy sources as soon as possible.

On the other side of the argument is a small group of scientists that believe the forecast models are wrong and over-estimate the rate at which the earth is warming and under-estimate the role natural variation plays in the current warming trend. The obvious term for them may be ‘climate non-alarmists’ but I call them climate realists. They don’t deny the science, even as they question the panic mode endorsed by the climate alarmists.

Climate realists refuse to go away to the consternation of many in the climate science community. The reason revolves around the term: equilibrium climate sensitivity (ECS). And if a recent climate study published in the Journal of Climate is an indication, its actual value is still uncertain.

The ECS estimate is a summary of the eventual warming of the planet’s surface from a doubling of CO2 once the world’s climate system has adjusted to the higher levels of CO2. Estimates of the ECS are important because they drive conclusions on whether the globe will experience catastrophic temperature increases by the end of the 21st century. If the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is correct, global temperatures will be 3.1°C higher than pre-industrial levels by 2100.

But a new study in the Journal of Climate is now suggesting the IPCC’s ECS estimate might be too high by a factor of two.

Dr. Judith Curry, a climate scientist and former Chair of the School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences at the Georgia Institute of Technology, and Nicholas Lewis, a retired financier with a background in mathematics and physics, report in their study an ECS estimate of 1.66°C (5–95% uncertainty range: 1.15–2.7°C).

Why does their model not run as hot as IPCC global temperature models? They say for two reasons: their model (1) takes into account historical atmospheric and ocean temperature trends since the mid-19th century, and (2) draws on new findings since 1990 of how atmospheric ozone and aerosols are likely to affect global temperature trends.

Their critics, of which there are many, cite other reasons for their ‘less warm’ temperature forecasts.

Climate scientist Steven Sherwood, commenting on an earlier study by Lewis using a similar methodology to the Lewis and Curry 2018 paper, claims Lewis cherry-picks evidence and methodologies that “point toward lower sensitivity while ignoring all the evidence pointing to higher sensitivity.”

Dr. Drew Shindell, a climate scientist at NASA, has found in his research that studies based on observed warming (such as the recent low climate sensitivity study Lewis and Curry) have underestimated the sensitivity because they did not account for the greater response to aerosol forcing.In other words, Lewis and Curry’s temperature model is too simplified to make reliable forecasts.

There is another reason to be cautious of Lewis and Curry’s 2018 research finding of lower climate sensitivity to CO2.

“It’s particularly important not to fall victim to single study syndrome for this type of study,” contends Dana Nuccitelli, an environmental scientist at a private environmental consulting firm in the Sacramento, California area. “It can be tempting to treat a new study as the be-all and end-all last word on a subject, but that’s generally not how science works. Each paper is incorporated into the body of scientific literature and given due weight.”

Dr. Malte Meinshausen, of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research in Germany and the University of Melbourne’s School of Earth Sciences, cautioned about over-interpreting lower estimates for climate sensitivity. If these lower ECS estimate are correct it “only results in a delay of less than a decade in the timing of when the 2°C threshold would be crossed,” according to Meinshausen.

Climate alarmists on a principled level believe the relationship between science and public policy demands greater weight be placed upon the research estimating higher levels of climate sensitivity.

“The policy should be about avoiding risk,” Meinshausen told The Guardian in 2014. “If we shift policies to a more relaxed approach and then find the higher estimates are more likely, then we have locked ourselves into a pathway of high fossil fuel use and eliminated our chance of staying below two degrees of global warming. We want a good chance of avoiding catastrophic climate change — not one that’s like guessing the toss of a coin.”

But Meinshausen’s viewpoint begs the larger question, why should scientists care about the risks of global warming to human beings? The earth doesn’t care if humans can live comfortably on it. The laws of nature didn’t require congressional approval or a social consensus before they took effect. So why do climate scientists need to consider “risks to humans” when talking about their models of the planet’s climate system? A scientist’s first task is to get the science right. To consider the human risks as they build the science is to introduce systematic bias into the process. Using science to justify dramatic public policy measures to counteract global warming brings it own set of risks:

- Is it possible we could spend trillions, cause tremendous disruptions in the global economy, and still not impact the current global warming trend? (Curry says, “Yes.”)

- Is it possible mankind’s current rapid conversion to renewable energy has already put us on a path to successfully mitigate and adjust to the higher order impacts of global warming? (That is an argument I summarize here)

The mainstream media’s oft-repeated exaggeration that the climate science is settled only hardens the partisan divide between the scientific community and defenders of the fossil fuel economy. And, besides, when is science ever settled? Einstein is still defending his theories of general relativity and special relativity.

Though a critic of Lewis and Curry’s research, one climate scientist acknowledges the climate science, particularly with respect to climate sensitivity measures, is not settled. “Climate sensitivity remains an uncertain quantity,” according to Professor Piers Forster of the University of Leeds, who published a study with Jonathan Gregory of the University of Reading in 2006 that gave an ECS estimate of 1.6°C for a doubling of CO2.

Morevoer, if Lewis and Curry’s ECS estimates were the lone outlier, their research would be easier to dismiss. But their estimates don’t stand alone. In the July 2017 issue of Nature Climate Change, climatologists Thorsten Mauritsen of the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology and Robert Pincus of the University of Colorado reported an ECS of 1.5°C (0.9–3.6°C, 5th–95th percentile).

And one of the original ‘climate realists,’ Dr. Richard S. Lindzen, a climatologist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and a colleague, Yong-Sang Choi of Ewha Womans University (Seoul, Korea) reported an ECS estimate around 1.5°C in their 2011 study.

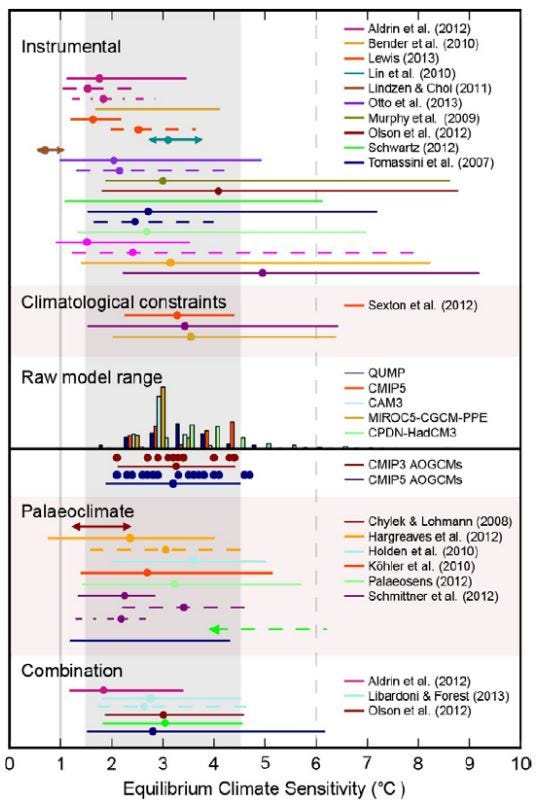

As seen in the chart below, most recent model estimates of the ECS are around 3.0°C, twice that of Curry and Lewis (2018), Mauritsen and Pincus (2017), and Lindzen and Choi (2011). There is real variation in this chart that simply cannot be dismissed as the sole product of the global warming deniers.

At this juncture, the safer bet may be to assume the ECS estimates around 3.0°C are more accurate. However, scientific insurgencies must start somewhere and it is becoming increasingly untenable for climate change alarmists to ignore research suggesting the planet may not be warming as fast as once assumed.

In addition, the global warming hiatus between 1998 and 2015 remains at the center of the debate regarding the relative contribution of man-made sources of greenhouse gases and natural variation. If man is responsible for 100 percent of the global warming since 1950, as suggested by NASA climate scientist Gavin Schmidt, how do we explain the pause without reference to natural variation? And can we assume natural variation cancels itself out over the long-run, as suggested by climate alarmists, leaving only anthropogenic factors as the cause of current global warming?

“Numerous recent research papers have highlighted the importance of natural variability associated with circulations in the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, which is now believed to be the dominant cause of the (warming) hiatus,” Curry told the U.S. House Committee on Science, Space and Technology in 2015. “If the recent warming hiatus is caused by natural variability, then this raises the question as to what extent the warming between 1975 and 1998 can also be explained by natural climate variability.”

“Climate models do not simulate correctly the ocean heat transport and its variations,” said Curry.

In contrast to Meinshausen’s belief that government’s should err on the side of caution and promote dramatic measures to combat global warming, Curry takes a different approach:

“We should expand the frameworks for thinking about climate policy and provide policy makers with a wider choice of options in addressing the risks from climate change,” said Curry. “Pragmatic solutions based on efforts to accelerate energy innovation, build resilience to extreme weather, and pursue no regrets pollution reduction measures have justifications independent of their benefits for climate mitigation and adaptation.”

Lewis and Curry are not deniers of anthropogenic global warming. By including them in the three percent category of global warming deniers, the mainstream of the climate science community is doing their discipline a disservice.

While Lewis and Curry have undoubtedly accepted research monies from wealthy interests that do deny the realities of global warming, their climate research is credible enough to be published in peer-reviewed journals and wholly consistent with the consensus that humans have impacted the global climate through the production of greenhouse gases. Their heresy is that they believe the pace of this warming and the relative contribution of humans versus natural causes remain open questions.

They may be wrong. But criticism of their research should be solely driven by scientific considerations, and not by political agendas. Climatologist Michael Mann’s famously direct disrespect for a congressional committee’s inquiry into global warming in 2017 highlights the poisonous environment within which climate science now operates.

As Curry told a previous U.S House committee on climate science in 2015:

“ I am increasingly concerned that both the climate change problem and its solution have been vastly oversimplified. My research on understanding the dynamics of uncertainty at the climate science-policy interface has led me to question whether these dynamics are operating in a manner that is healthy for either the science or the policy process.”

Bill Ritter, Jr., a professor at Colorado State University and director of the Center for the New Energy Economy, recently suggested the controversies in the climate science are increasingly becoming irrelevant as market forces have moved decisively towards converting the U.S. to a clean energy economy.

“Today, renewable energy resources like wind and solar power are so affordable that they’re driving coal production and coal-fired generation out of business. Lower-cost natural gas is helping, too,” writes Ritter. “And, despite the Trump administration’s support of coal, a recent survey of industry leaders shows that utilities are not changing their plans significantly.”

Climate alarmists can be largely thanked for the positive trends in renewable energy.

Assuming utilities continue in their efforts to convert from fossil fuels to renewables, climate scientists should find it easier to free themselves from the partisan squabbles that presently loom over their research and, instead, return to what Thomas Kuhn called “normal science,” where the regular work of scientists is in theorizing, observing, and experimenting within a settled paradigm or explanatory framework.

The fact that research by climate realists such as Lewis and Curry is now regularly appearing in peer-reviewed scientific journals is evidence that “normal science” is returning to the climate science community.

The better news is, in twenty or thirty years, we will know who got the climate science right and who didn’t. That’s how science should work.

K.R.K.

{Send comments to: kkroeger@nuqum.com}

About the author: Kent Kroeger is a writer and statistical consultant with over 30 -years experience measuring and analyzing public opinion for public and private sector clients. He also spent ten years working for the U.S. Department of Defense’s Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness and the Defense Intelligence Agency. He holds a B.S. degree in Journalism/Political Science from The University of Iowa, and an M.A. in Quantitative Methods from Columbia University (New York, NY). He lives in Ewing, New Jersey with his wife and son.