By Kent R. Kroeger (Source: NuQum.com, August 23, 2017)

{ Feel free to send any comments about this essay to: admin@nuqum.com or kentkroeger3@gmail.com}

We often fail to see what we don’t expect to see. This is one of experimental psychology’s most durable research findings and the phenomenon has been given a name: inattentional blindness.

It is one reason patients should always get more than one physician to read their x-ray results. It is hard to find something you aren’t looking for.

This bias is displayed in a recent political essay by Eric Levitz for New York Magazine who concludes, after citing a wide range of political science research, that the “Democrats can abandon the center — because the center doesn’t exist.”

It’s a bold statement — and not without some merit — but it has one serious problem: It is not supported by any empirical data, including the data he references.

THERE IS A POLITICAL CENTER-OF-GRAVITY, IF YOU LOOK FOR IT

Relying heavily on Dr. Lee Drutman’s analysis of the The Voter Study Group‘s recent 2016 post-election survey (fielded by YouGov.com), Levitz concludes it would be a strategic mistake for the Democrats’ party to move to the center in an attempt to regain the white, working-class voters (“populists”) purportedly responsible for Hillary Clinton’s defeat in the 2016 presidential election.

Levitz’ conclusion receives apparent visual support from one of Drutman’s graphs showing how 2016 voters spatially clustered along two dimensions: economics and social/identity issues:

Graphic Source: Lee Drutman (www.voterstudygroup.org)

In this graph, Clinton voters (in blue) are clumped almost exclusively in the bottom left quadrant (economic and social/identity liberals), while Republicans are divided between economic and social/identity conservatives and populists (economic liberals and social/identify conservatives).

Drutman’s interpretation of the above scatterplot is that the percentage of voters holding “centrist” views — right-of-center views on economic matters and left-of center views on “identity” issues — amounts to only 3.8 percent of the electorate. “Populists” — defined by their left-of-center views on economic matters and right-of-center opinions on “identity” issues — account for about 29 percent of the electorate, according to Drutman.

Though I strongly disagree with Drutman’s two-dimensional method for defining the political ideological groups, even his atheoretical, blunt force categorizations show one-third of the American electorate (in presidential elections, at least) are inadequately represented by the ideological purists from both parties. This hardly supports Levitz’ argument about a non-existent center.

Given his skepticism about the political center, Levitz says the Democrats can afford the risks associated with moving leftward. His prima facia support for this advice derives in part from Drutman’s finding that 45 percent of the electorate are “liberals” (compared to only 23 percent that are “conservatives”). If “liberals’ are both ideologically homogeneous and numerous, by extension, says Levitz, there is little electoral value in appealing to a small (possibly fictional) number of “moderate” swing voters. The Democrats simply need to get their supporters out to vote to win elections, according to Levitz. Furthermore argues Levitz, citing research by political scientists such as Gabriel Lenz, voters are so poorly-informed and inconsistent on policy issues that making intellectual appeals to them based on “centrist” policies will likely fall on deaf ears.

Levitz writes: “If swing voters aren’t actually ideological moderates, but relatively uninformed citizens who switch allegiances on the basis of identity appeals, economic conditions, and/or candidate charisma — while partisans take their policy positions from party leaders — then there’s little reason to believe that Democrats would inevitably lose votes by endorsing Medicare for All instead of the Affordable Care Act; free public college instead of tuition subsidies; or a federal job guarantee instead of infrastructure spending.”

The arrogance displayed in Levitz’ quote helps explain why Democrats continue to lose most elections in this country. When you view half of the voting population as essentially morons, needless to say, you tend not to get their support on election day. Mitt Romney’s writing off of ’47 percent’ of voters in 2012 didn’t work well; it won’t work any better for the Democrats.

Romney’s ’47 percent’ gaffe notwithstanding, Republicans tend to portray partisan Democrats as “hopeless idealists,” “elitists,” or, more recently, “globalists.” Those are attributes some people wear with pride. However, calling voters “uninformed” (which Democrats use euphemistically for “moron,” idiot,” “inbreed,” or “probably a neo-Nazi racist”) does not make Democrats’ outreach to swing voters any easier.

To Levitz’ credit, he draws in a broad range of political science research to support — and sometimes even challenge — his primary thesis. An example of the latter is his acknowledgement that many voters can be mobilized to vote against candidates they perceive as ideologically extreme. Political writer Dan McGee lists this phenomena as the fifth commandment for elections in the age of hyper-partisanship.

At a minimum, adopting policy stances attractive to the Democratic Party’s activists, such as endorsing Medicare for All, free public college, and federal job guarantees, invites the GOP to frame the election as one between fiscally-conservative Americans versus Democratic extremists. At worst, it can lead to an electoral meltdown for the ‘extremist’ side (think 1964 — LBJ-Goldwater).

Levitz’ confidence that the majority of Americans support the progressive agenda — and that is questionable — assumes the GOP has no degrees of freedom left to respond to the Democrats’ move leftward. If the Drutman scatterplot tell us anything it is that the Republicans attract voters across a broader range of opinions, beliefs and attitudes.

Elections are a complex balancing act, particularly at the presidential level. Ideologically distinctive politicians risk being labeled an ‘extremist” or “out-of-touch” or a “pawn of special interests.” Take your pick. Yet, diving to the center on the important issues is not a proven strategy either. Recent European voter research by Stanford researcher Toni Rodon shows that the “political middle is less likely to vote when parties do not distinguish themselves ideologically.” Ronald Reagan and his pollster, Richard Wirthlin, realized this relationship in the mid-70s when Reagan gave his famous “bold colors, no pale pastels” speech.

The Democrats can’t build market share by watering down its ideas or mission. Reagan and Wirthlin knew that party-building is akin to brand-building. Distinctive brands that differentiate themselves from the competition on the important dimensions can become strong, growing brands. But the Democrats can’t build a strong brand through excessive narrowcasting either. It may promote loyalty among its strongest partisans, but always risks alienating its marginal supporters. And, contrary to Levitz’ interpretation of the data, there are plenty of marginal Democratic voters.

From a strategic branding point-of-view, the conclusion from Drutman’s work should have been that there is more attitudinal diversity within Republican voters than within Democratic voters. F.H. Buckley has a much better perspective than Levitz on how to read Drutman’s analysis of the Voter Study Group survey.

“Most (Trump) voters, they’re not right-wing crazies…they’re middle of the road types. but solidly patriotic Americans…and that’s the sort of thing that the liberal Democrats simply haven’t gotten,” Buckley said in a recent interview with the editors of American Greatness. “Unless you sign onto all of their (Democratic) issues, their social agenda, you’re going to be excluded.”

If that is true (and our the 2016 American National Election Study [ANES] analysis supports that conclusion as well), without a major brand re-imaging effort, its the Democrats that may be approaching maximum market share, not the Republicans.

IF AMERICA IS SO LIBERAL-MINDED, WHY DO DEMOCRATS LOSE SO MANY ELECTIONS? BAD BRANDING & STRATEGY

The basic insight from game theory’s Nash Equilibrium is that, in a multi-player game, one single player cannot predict a game’s outcome without taking into account the decision-making calculus of every other player in the game., who must also take into account every other player’s decision calculus.

This game theory result may sound like common sense, but most political analysts (including Levitz and Drutman) don’t seem to understand how to incorporate this maxim into practice. In concrete terms, it means any strategic analysis about what the Democrats should do in 2018 (and beyond) must also consider how the Republicans must move forward and how that decision could, in turn, impact the Democrats’ strategy. The Nash Equilibrium reminds us that strategy-building is iterative (but not endless). At some point, every player can estimate his or her optimal strategy — until some exogenous event (e.g., the economy) changes the conditions of the game.

The rigor Levitz and Drutman apply to determining the best policy strategy for the Democrats moving forward should have also been applied to the question, “If Democrats move farther to the Left, what do the Republicans need to do in response?” That answer most likely changes the Democrats’ original strategy decision.

Any claims of knowing the definitive answer as to what one political player should do to win elections is fanciful dream weaving unless it includes the same attention to the other political player’s strategy. If American electoral history tells us anything, its that one party will never be far outside the reach of the other.

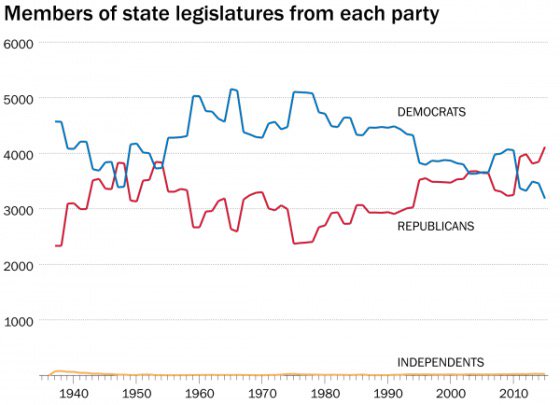

Which makes the Democrats’ current nadir in representation within our nation’s political institutions even more puzzling. What is causing this secular decline?

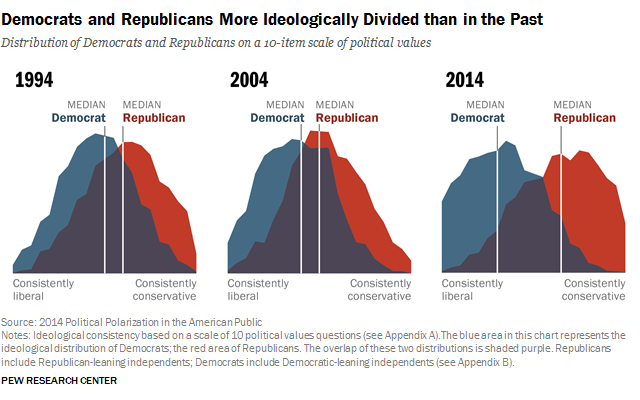

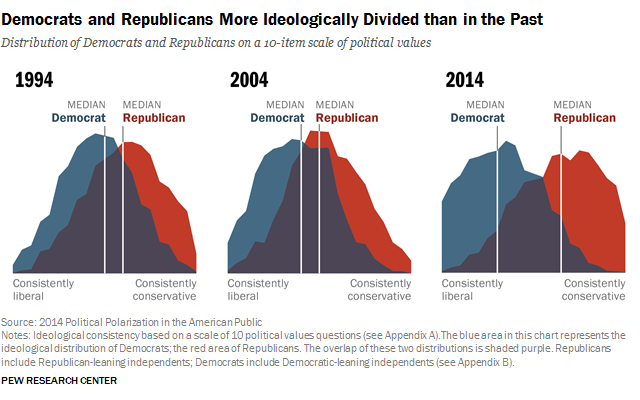

Is it the (arguably) increasing polarization of American voters? If so, how does moving even farther to left change things in the Democrats’ favor? Increasing polarization could just as easily form the strategic basis for a “move-back-to-the-center” movement (see Pew Research graphic below).

As the Pew Research data shows, even in a polarized electorate (2014), there are plenty of Republicans in the left-tail of its voter distribution (and likewise for the Democrats in the right-tail of their distribution). A minor shift in support from voters in those two tails changes electoral outcomes.

(In the context of corporate brand-building, I highly recommend Jan Hofmeyr and Butch Rice’s book, Commitment-Led Marketing, which combines chaos theory with religious conversion research to help companies build effective branding strategies for market share and customer loyalty growth).

The increasing structural disadvantages the Democrats face must also be considered when building strategy. Incumbency advantages, geographic clustering of Democratic voters, gerrymandering, and voter suppression laws all work against the Democrats from winning elections.

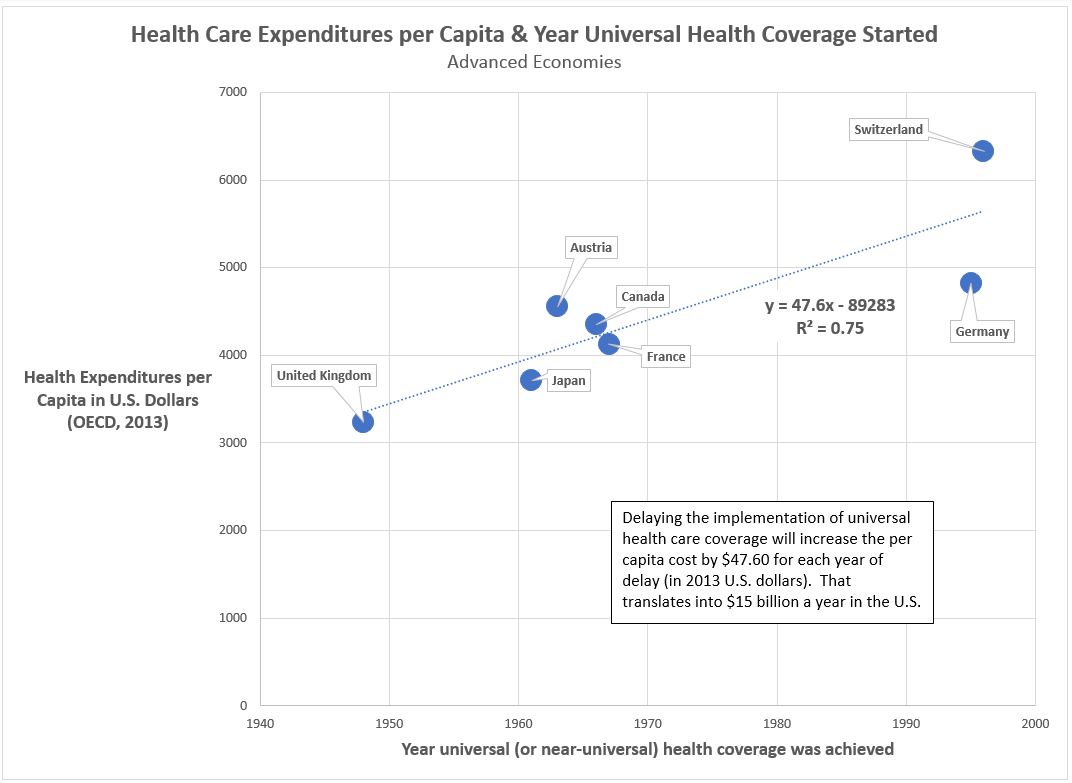

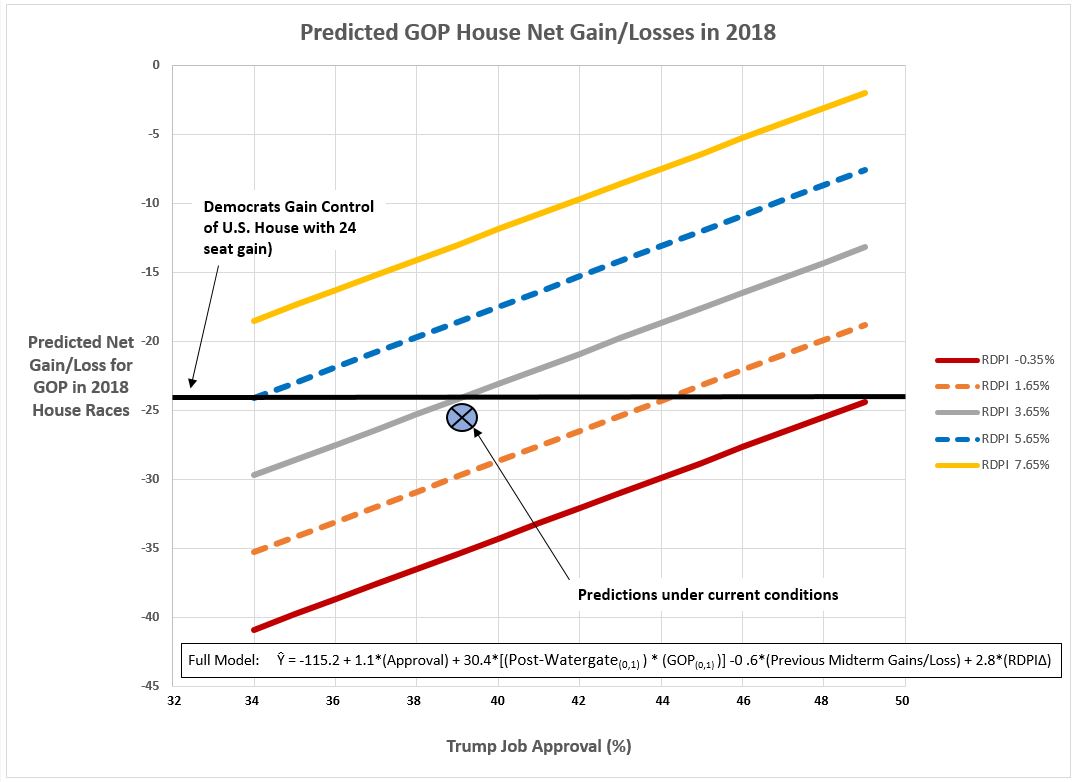

An Associated Press analysis estimates that the Republicans benefit from an efficiency gap of nearly 3 percent in U.S. House races, “allowing them to win three more seats than they would have expected to win given their share of statewide votes.” Its not a large advantage considering NuQum.com currently estimates the GOP will lose around 30 U.S. House seats in 2018 given current Trump approval levels and state of the economy — more than enough for the Democrats to re-take control of the U.S. House.

Structural disadvantages, while real, don’t seem large enough however to fully account for why the number of elected Republicans is at or near historical highs. At some point, Democrats need to consider their ‘brand’ as part of the problem. And not just so we can hear the ‘we need to sell ourselves better’ trope.

It’s not just how Democrats are selling the brand, its what the brand stands for that may inhibiting the party’s success.

To argue that we live in a left-leaning country and progressive policy ideas are better anyway, as Levitz does, fails to address why only about a quarter of Americans are willing to call themselves ‘liberal.’ Even if self-reported ideology is a not a powerful variable in vote prediction models, it does reflect an ongoing reality in this country that the word ‘liberal’ remains a dirty word.

Forgive me, but suggesting the Democrats can address that problem by becoming even more liberal fails the smell test.

Which brings us back to this essay’s original question. Are analytic partisans like Levitz and Drutman deceiving themselves into thinking the political center is a fiction and therefore is of little target value?

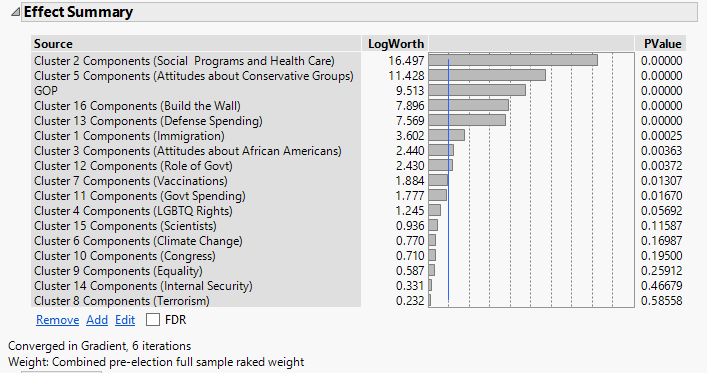

The answer, I believe, is an emphatic, yes, and I lay the blame on analyses like Drutman’s on the YouGov-administered survey for the Voter Study Group.

This is not a criticism of YouGov‘s methods*, survey research in general, quasi-experimental designs, cross-sectional samples or of statistical techniques such as principal component analysis. This problem is much deeper, more pervasive, and infinitely harder to address than any of those methodological issues. The problem is rooted in an institutional legacy of bias among researchers (e.g., confirmation bias, inattentional blindness, etc.) that has driven the social science research agenda since the 1960s. I would even suggest that Democrats and liberals have a psychological need to believe the world thinks like they do and is therefore safe.

(* A brief discussion at the end of this essay covers some of YouGov’s methodological issues)

That is why research like Drutman’s is so comforting to the Left. It confirms their view of the world. Unfortunately, Drutman’s analysis of The Voter Study Group (YouGov) survey confuses the statistical artifacts of his analytic choices for the real world. And while it may confirm the progressive Left’s worldview, it encourages biased conclusions and actually trammels their long-term electoral prospects.

It is therefore worth a brief discussion of the serious flaws in Drutman’s work.

DRUTMAN”S RESULTS ARE ARTIFACTS OF HIS METHODOLOGY

(1) Post-election surveys make better mirrors than crystal balls

Post-election surveys typically ask respondents about the issues prevalent in the previous election. It shouldn’t surprise anyone, therefore, when this research finds that American voters are well-differentiated when collectively summarizing their survey responses. Levitz, himself, mentions the research explaining how elections serve as cues to help voters align their party and candidate preferences with their issues stances.

“Most voters develop a preference for one of the major parties — typically, on the basis of the historic allegiances of their family, region, economic class, racial group, or religious community — and then take their ideological cues from their party’s leaders (when they don’t ignore the details of policy altogether), writes Levitz.

Scratch the surface of voters’ increasingly polarized issue positions, such as changing how an issue is framed, and you find their views are far from immutable. Levitz provides excellent examples of how issue framing can dramatically change apparent policy preferences.

When voters respond to survey’s like The Voter Study Group’s, they are partly reflecting back on how issues and candidates were framed in the most recent election. A new election with new candidates and issues and you may get different responses.

There is no better example of this process than how attitudes on American trade agreements shifted between the 2008 and 2016 presidential elections. In 2009, 57 percent of Republicans thought free trade agreements were a “good thing.” After the 2016 election, only 32 percent had the same opinion. While this is not a direct measure individual-level opinion change, that magnitude of change is too large to be solely the function of different Republican voting populations.

That is not to say voters don’t genuinely hold those beliefs. It is saying those survey-reported attitudes and beliefs are endogenous to the system itself and cannot be understood solely as independent factors in election outcomes. Change the election, candidates, issues, and frames and you can get different attitudes and beliefs.

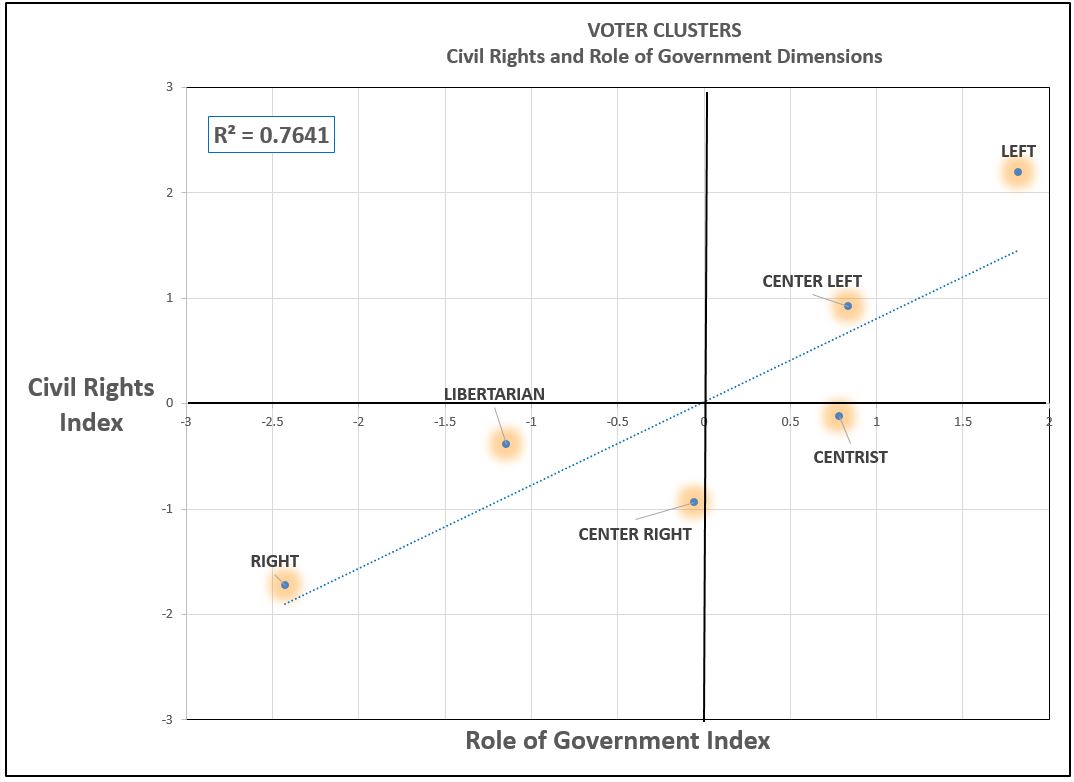

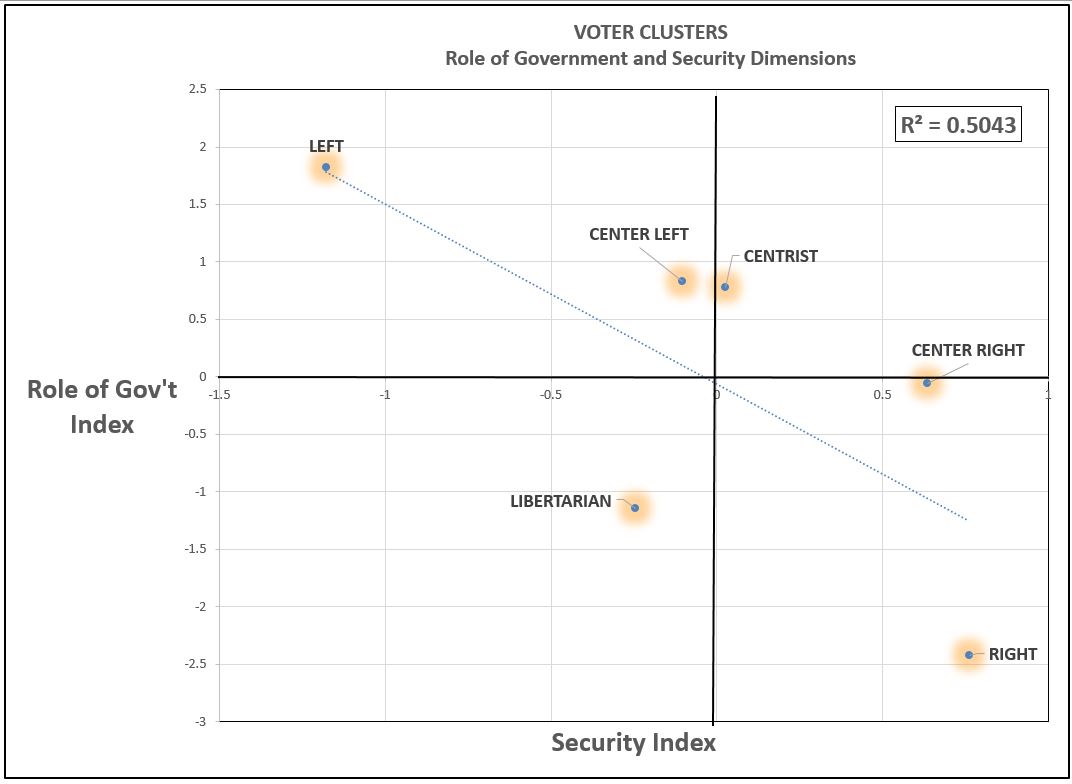

(2) Political ideology is a multi-dimensional construct

Political scientists eschew respondents’ self-reported political ideology and instead recommend measuring it based on respondents’ views on specific issues within two dimensions: social and economic. Social issues typically concern attitudes on such things as LGBTQ rights, abortion and the role of government in relieving social problems. The second dimension, economic issues, concerns such things as taxes, economic regulation and the distribution of income and wealth.

The problem with viewing political ideology as a two-dimensional construct, as Drutman’s analysis of the Voter Study Group/ YouGov data does, is that political ideology is a multi-dimensional construct. Drutman himself recognizes this fact.

“We should view politics across multiple issue dimensions,” writes Drutman. “Rather than simply describing political alignments in terms of “left” and “right,” I argue that we should understand that voters are not ideologically coherent (in that they endorse the party line across most issues), but instead have different mixes of left and right views across different issues.”

So why then does Drutman present something that is multidimensional as a two-dimensional phenomenon? Like most data analysts (myself included), analytic choices are often driven by a need to simplify the graphical presentation of complicated data relationships.

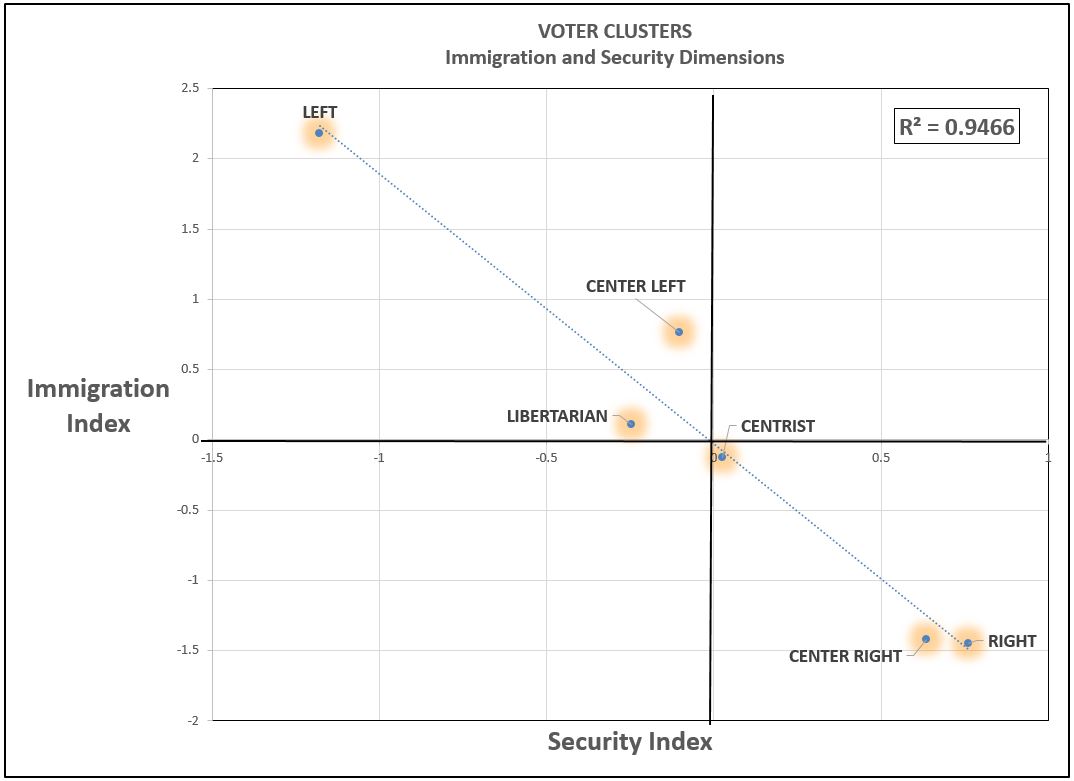

Take a closer look at Drutman’s scatterplot of 2016 voters. It is a two-dimensional plot — which if we added a third dimension (national security issues, perhaps?) the dots would need to move off the page, some more than others. In other words, it is likely that the apparent clumping of Clinton voters in the lower left-hand quadrant might be exaggerated by the two-dimensional plot.

It most certainly is exaggerated.

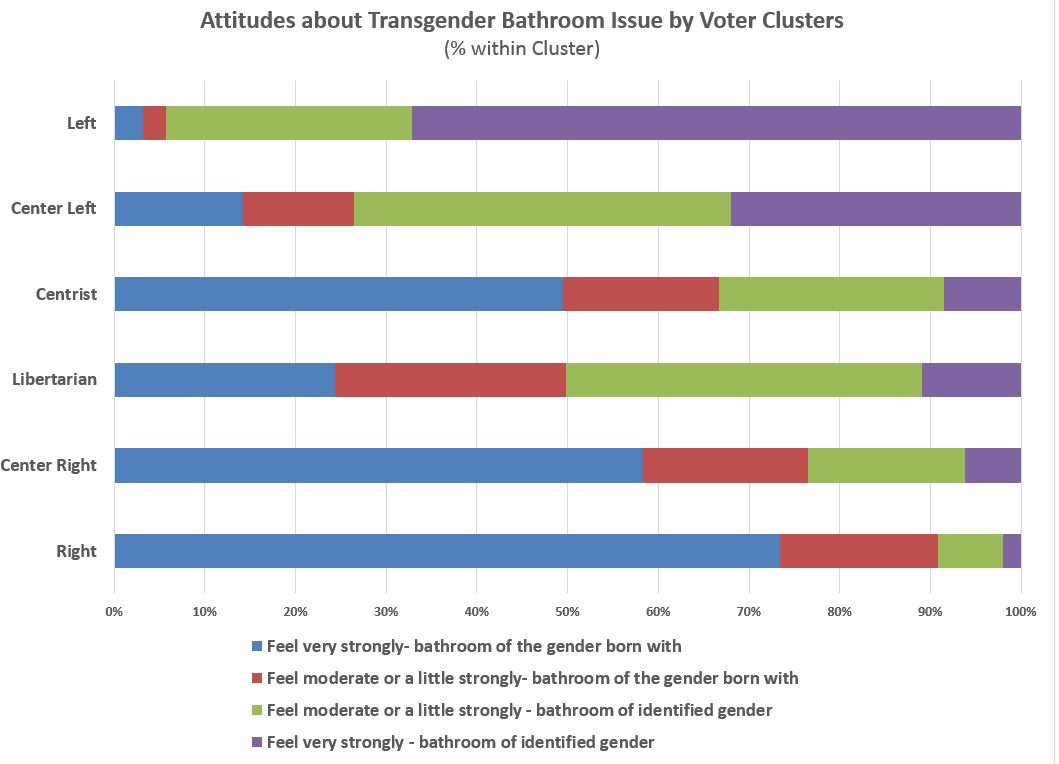

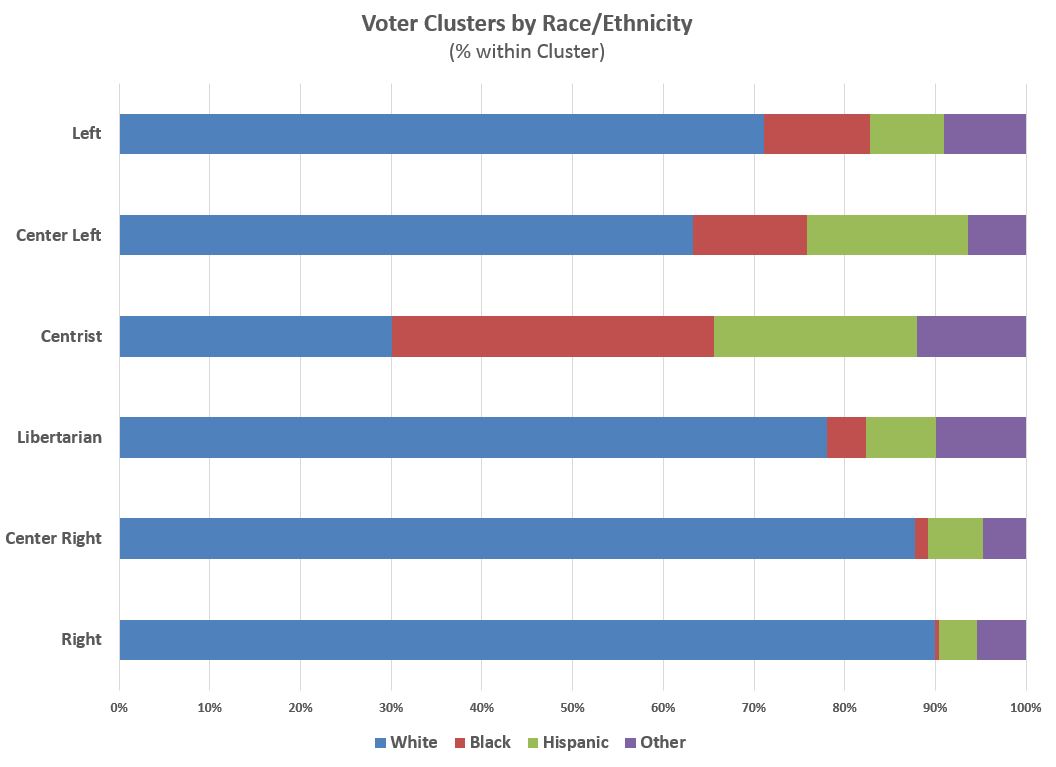

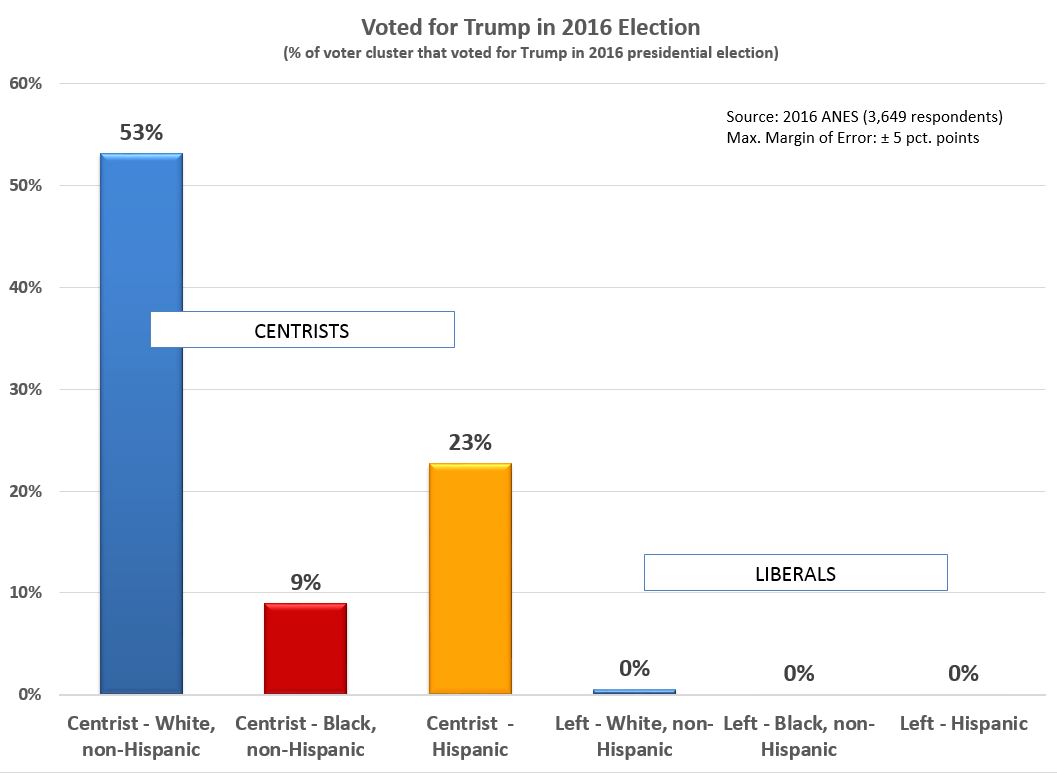

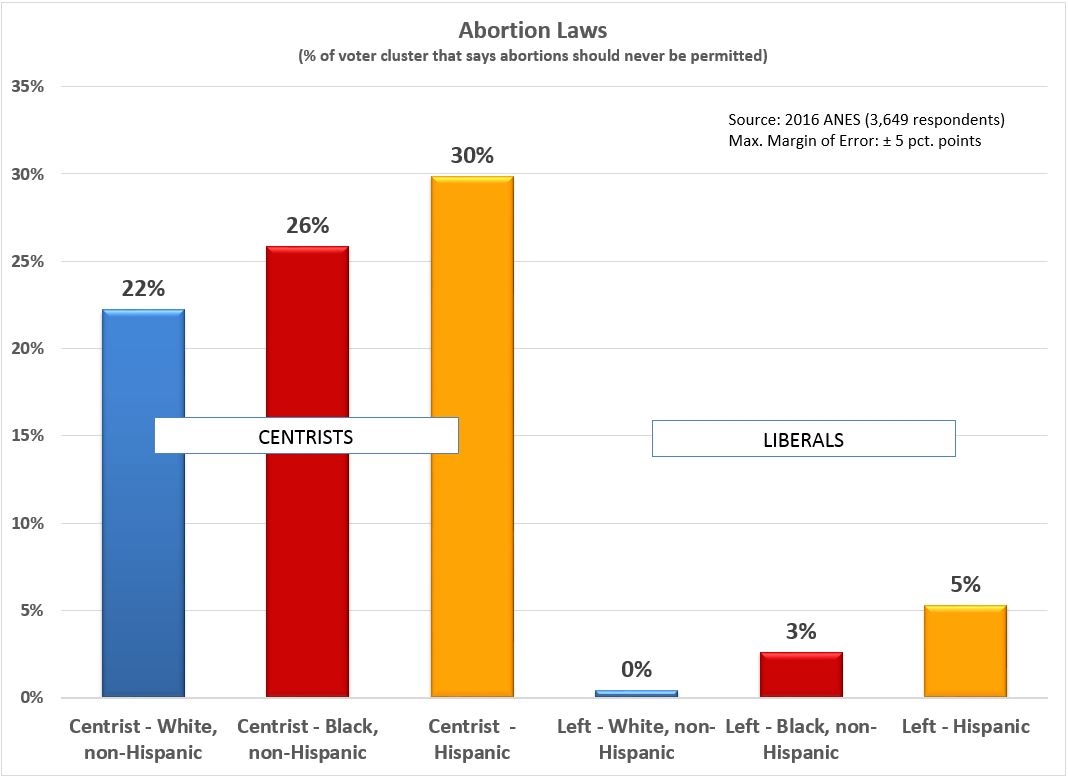

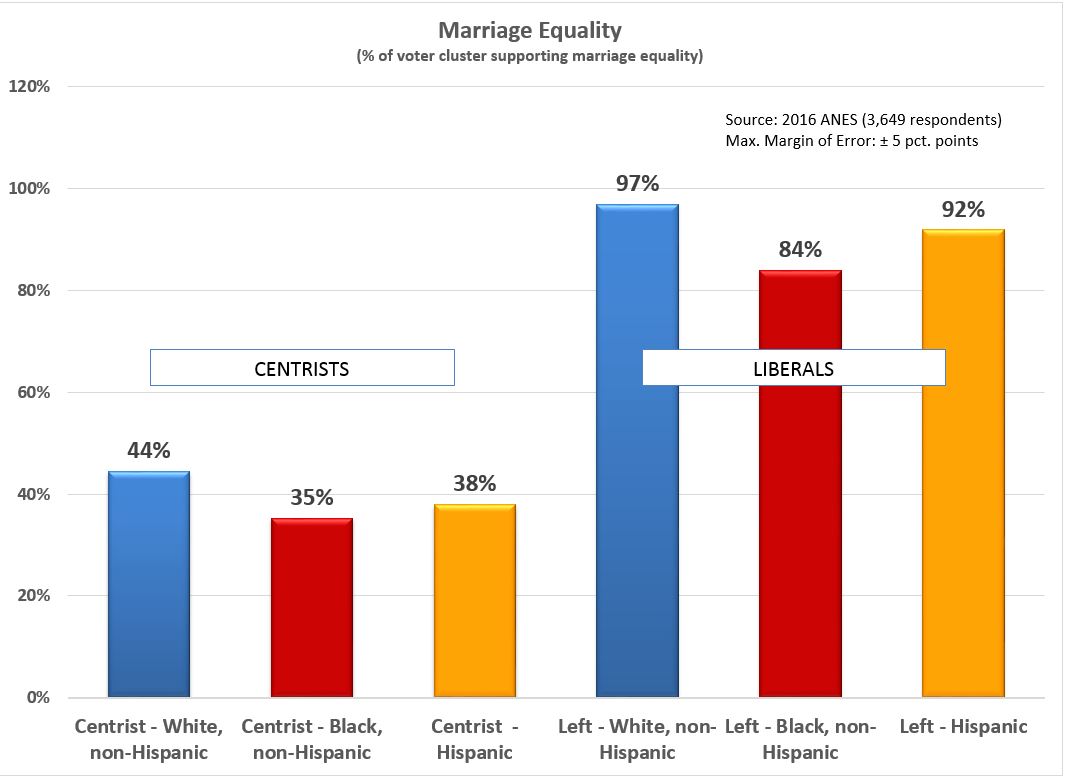

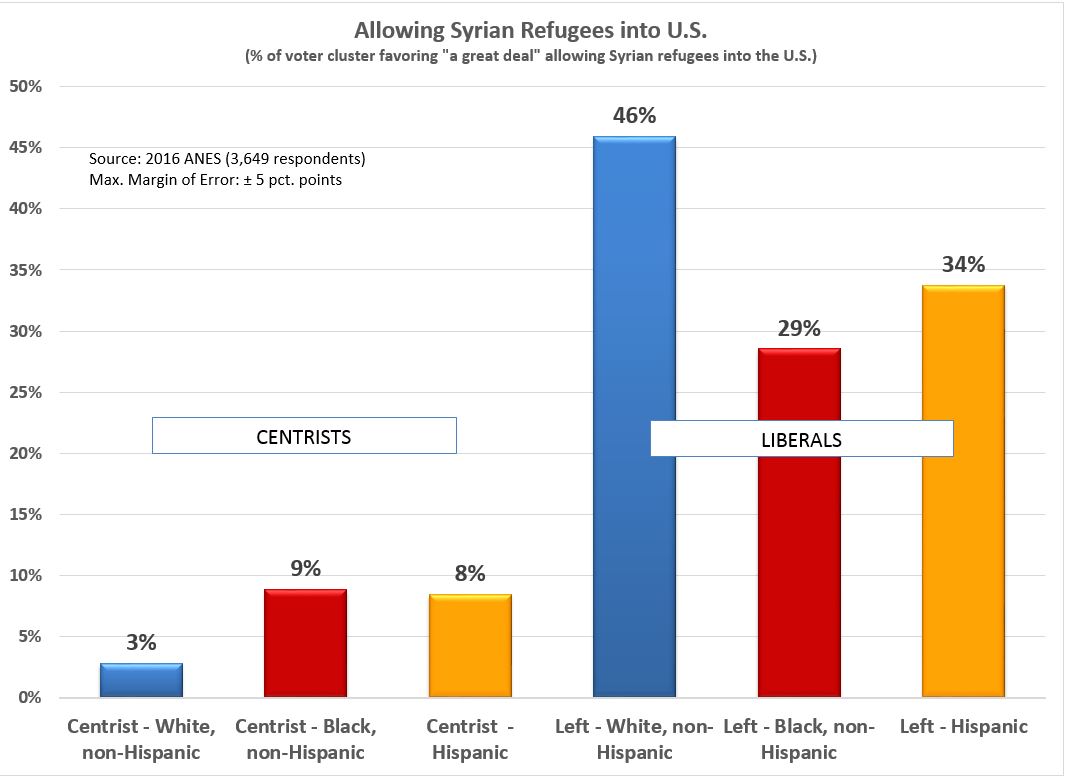

There is significant opinion diversity within Clinton voters. NuQum.com’s own analysis of the 2016 vote using data from the 2016 American National Election Study (ANES) shows Clinton’s support base draws from three major ideological clusters (Liberals, Center-Left, and Centrists).

A strategic Republican Party, if it still exists, will exploit this opinion diversity within the Democrats. While the emerging, near-permanent Democratic-majority-thesis was always an inappropriate interpretation of the political impact of U.S. demographic trends, it does demonstrate how difficult it will be for the Republicans to win elections with their 2016 electoral coalition. The demographic numbers don’t work for the GOP. Trump’s 2016 coalition will not be enough in 2020. {The Atlantic’s Ronald Brownstein offers an excellent summary of the demographic trends for both parties)

The Republicans will need to expand their base into identify groups they don’t currently perform well in. Upward economic mobility will help (particularly among Hispanics), but if I were a Republican, I would be very, VERY nervous about 2018 and 2020.

But this essay is about helping the Republicans. Its about the Democrats who, I fear, have chanted themselves into a collective stupor that assumes Trump will be forced from office, they will re-take the U.S. House in 2018, and a Democrat (probably Kamala Harris) will be elected president in 2020. The first prediction won’t happen…the second prediction has a better than even chance…and we just don’t have enough information to say anything meaningful about 2020.

Essays like Levitz’s relying heavily on research like Drutman’s don’t help the Democrats. It keeps them over-confident and arrogant.

(3) Absolute versus Relative Measures — You Don’t Have to Choose

There are many ways to transform and manipulate data so that it can be effectively analyzed. Drutman made some important decisions in analyzing the Voter Study Group survey.

“The measures here are’absolute’ measures as opposed to ‘relative,” writes Drutman. “I took the responses to the VOTER Survey questions as given, rather than rescaling the indexes to set the median score at zero.”

Drutman’s “absolutist” choice has clear advantages. For one, It makes his results easier to interpret. When “-1″ means support for a liberal policy and ‘1” means support for a conservative approach (and zero, of course, is neutral or unsure), that is easy for readers to digest. Secondly, it simplifies comparing public opinion over time on specific issues (or issue dimensions) over time.

Unfortunately, his decision also as serious ramifications, as acknowledged by Drutman himself when he states, “While (the relativist) transformation would have made for a more symmetrical presentation, it ignores the fact that Americans may hold left-of-center views on some issues and right-of-center views on other issues.”

Well, actually, he is wrong on that last point. The “relativist” approach doesn’t ignore that Americans can hold both left-of-center and right-of-center opinions. It does the opposite. It forces all issues onto a left-right continuum.

Look one more time at Drutman’s scatterplot above that uses the “absolutist” approach. Without needing Drutman’s original data, it is possible to imagine how the “relativist” approach would have changed this scatterplot. It would have simply centered the dots in the chart.

The “relativist” approach is answering a slightly different question than the “absolutist” approach. Where the “absolutist” asks where American voters fit along a pre-determined scale, the “relativist” asks where American voters fit relative to each other.

In my opinion, the “relativist’ approach is more appropriate for strategy-building because it allows every item to be assessed on a level playing field.

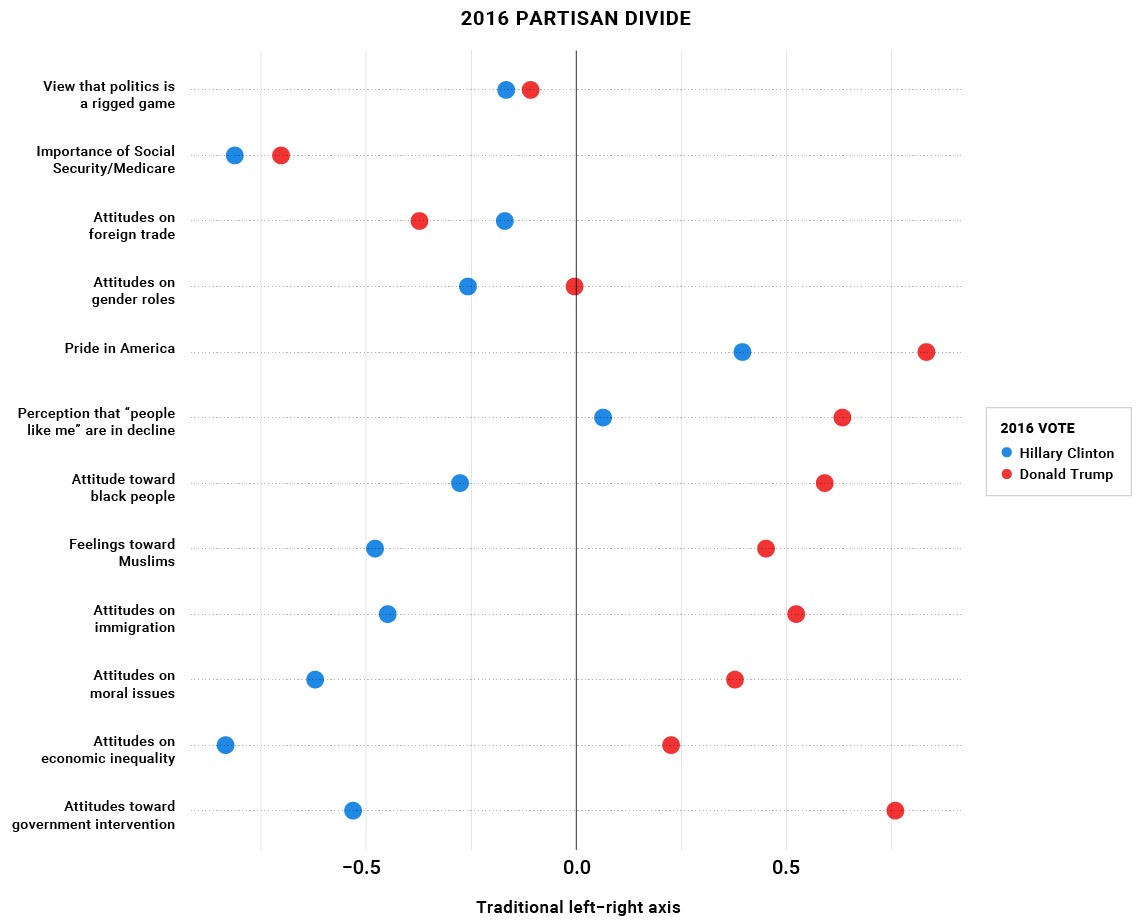

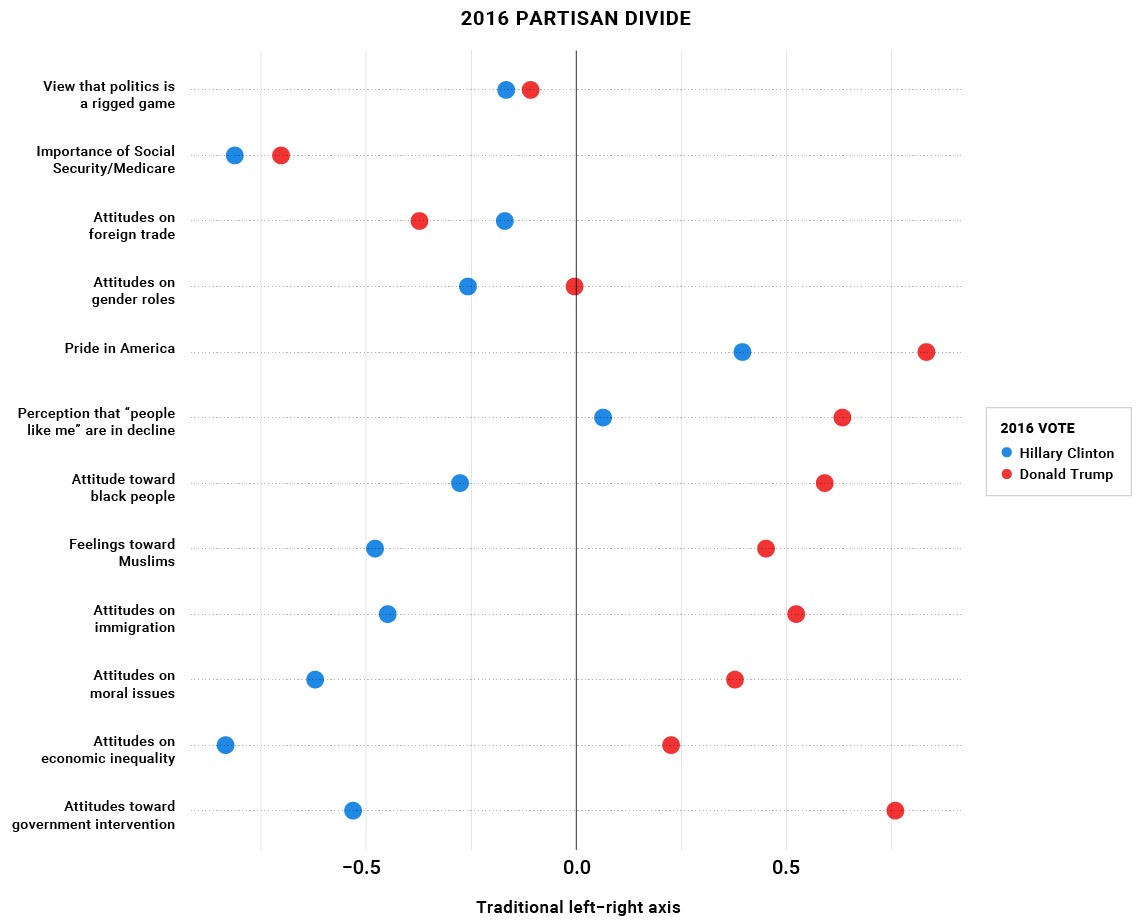

From Drutman’s summary of the Voter Study Group survey, the chart below shows the mean values among Clinton and Trump voters for each of the derived issues dimensions within the survey. Two of the dimensions (“Perception that people like me are in decline” and “Pride in America”) are particularly interesting in that the group means are all above zero — implying both Clinton and Trump voters hold traditionally conservative opinions on these two dimensions.

Graphic Source: Lee Drutman (www.voterstudygroup.org)

Drutman’s interpretation of this data feature is especially telling about his own ideological predispositions:

“Trump supporters tend to have more pride in America than Clinton supporters do, and they are more likely to think that their group is in decline. However, these divides are not as significant as many media narratives portrayed them to be.”

Really? Does Drutman actually demonstrate — statistically — that the “Pride in America” gap is more or less significant than the gaps for the other issue dimensions? It may be true, but you can’t judge Drutman’s assertion based solely on the “absolute” scale values for the two voter groups. It is entirely possible small “absolute” differences can have large effect sizes compared to other items with larger “absolute” differences.

Indeed, it has been well established within the social sciences that effect sizes are not necessarily determined by “absolute” scale differences. They may be correlated — but it is not a deterministic relationship.Sometimes small absolute differences on survey scales can have dramatic effect sizes on dependent variables (i.e., presidential vote choice).

Drutman’s “Pride in America” dimension is a good example. It is stunning (to me) that almost half of Clinton’s voters are closer to the neutral response than the far right-end of the response scale on items such as: “I would rather be a citizen of America than any other country in the world.” Predictably, Trump voters are more likely to be close to the extreme right position. That is potentially a Pacific Ocean amount of difference between Clinton and Trump voters — even if, on an absolute scale, this difference is much less than the absolute differences on other issue dimensions.

It is very likely that a heavy dose of the social desirability bias is contaminating the “Pride in America” questions, such that, Democrats/Liberals are systematically pulled to the right-end of the survey item scale, irrespective of their true beliefs. That, of course, is merely an assertion on my part; but, my experience on surevy issues like this give me confidence that this survey’s ‘patriotism’ questions are soaked in response bias.

If Drutman’s goal is simply to describe differences in opinions within the 2016 presidential election, “absolute” differences are fine — even preferred — as they are more interpretable for readers. But others, such as Levitz, use this descriptive-level information for strategic assessments and Drutman simply doesn’t provide the kind of evidence needed to make those sorts of judgments.

Drutman’s blanket decision to use the “absolutist” approach should have been based on the empirical evidence on an issue-by-issue basis. On some issues, the ‘relativist” approach provides no new information and the simpler “absolutist” scale might be preferable. On other issues, such as ‘patriotism,’ it is probably a mistake to use an “absolutist” approach. It potentially buries the true ideological nature of voters’ opinions on such issues.

That is why I often use both ‘relativist’ and ‘absolutist’ approaches when analyzing survey data and make the specific choices (such as in respondent clustering or regression modeling) based on the analytic intent and empirical evidence.

By choosing one exclusively over the other, Drutman has tuned a blind eye to significant ideological diversity within 2016 American presidential voters.

So, with these major reservations about the Levitz and Drutman analyses on the record, what next? If Levitz has, in fact, misinterpreted the Drutman analysis, what should the Democrats do to prepare for the elections in 2018 and 2020? Move to the center? Move to the Left? Don’t move at all? Play it by ear? Make it up as you go along?

We invite you to peruse our analyses of the 2016 ANES data (here, here, and here) which include strategic recommendations for the Democrats. In the meantime, here are two broad stroke ideas the Democrats might want to consider.

THE DEMOCRATS NEED TO THINK THEY ARE PLAYING FROM BEHIND, EVEN IF THEY AREN’T (…THOUGH THEY ACTUALLY ARE)

Long-time White House correspondent Sarah McClendon, who covered Washington politics from Truman to Clinton, was once asked why she thought Republicans were more difficult than Democrats to interview. Her answer then, in 1996, rings even truer today: “They have an inferiority complex.”

She believed Republicans, by doctrine, put less value on government which, in turn, makes them less knowledgeable and defensive when confronted on its complexities. But others have suggested something much deeper in the Republican’s permanent siege mentality that prompts them to believe their party is in a continuous uphill battle to win the hearts and minds of American voters.

“Democrats remain relatively unexposed to (media) messages that encourage ideological self-identification or describe political conflict as reflecting the clash of two incompatible value systems (think Fox News),” political scientists Matt Grossmann and Dave Hopkins write. “Instead, the information environment in which they reside claims to prize objectivity, empiricism, and policy expertise.”

While their chronic insecurity does not work well for them when they are the governing majority (as they are now), it makes Republicans a more formidable foe during elections. Iowa State Senator Jeff Danielson, a centrist Democrat representing a Republican-leaning district, once told me the secret to being a successful political candidate is to always believe you are behind.

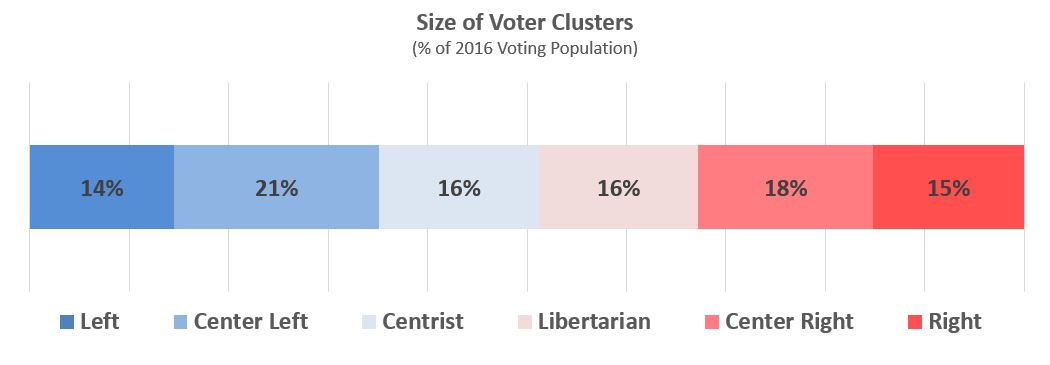

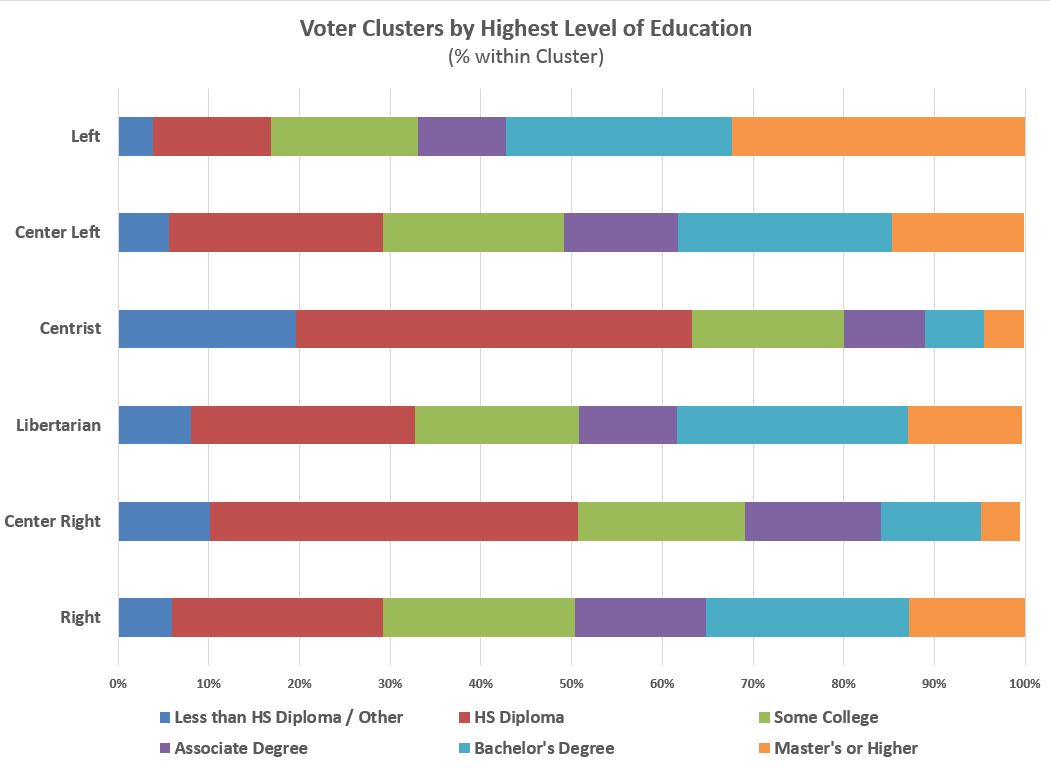

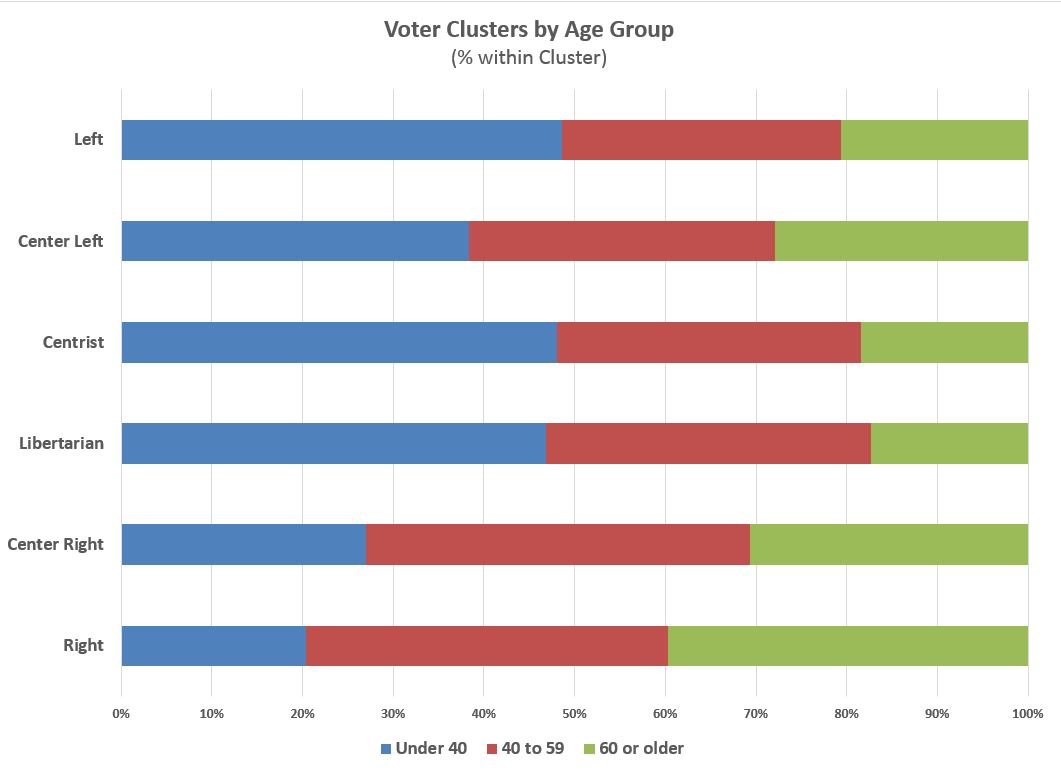

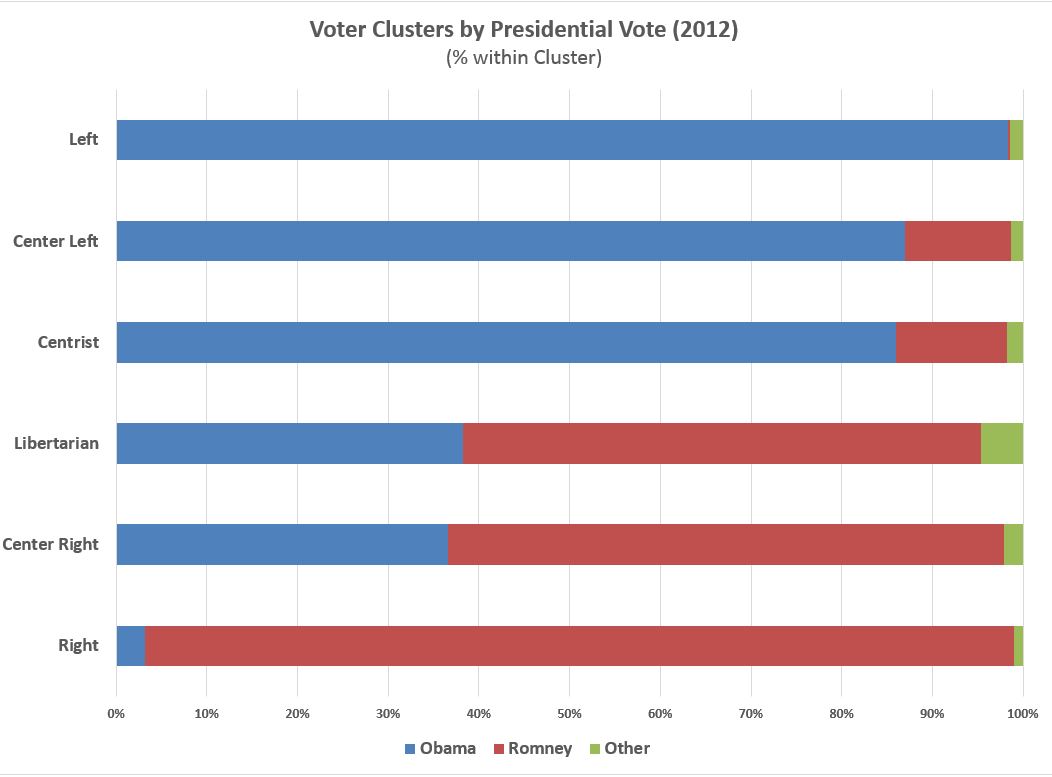

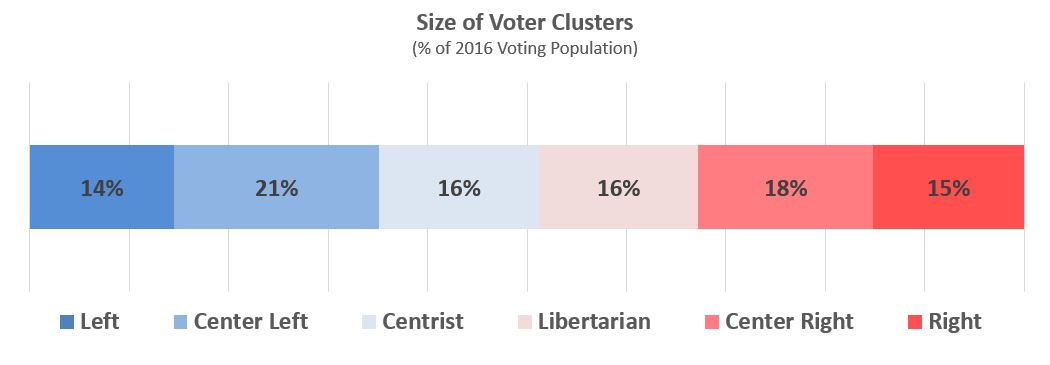

In the case of the Democratic collective, it shouldn’t be hard to convince them that they too are behind. But it seems to be. So let me re-share one of our findings from the 2016 ANES. Only 14 percent of the American electorate is consistently “liberal” (“Left” is our label preference) in their policy attitudes. A similar percentage are traditional “conservatives” (or the “Right” as we call them). Overall, the U.S. voting population is evenly split between left-leaning and right-leaning voters.

Graphic Source: NuQum.com

There is nothing in the Drutman/YouGov data that contradicts our findings from the 2016 ANES. In fact, we think our results match up nicely, even though we opted for the “relativist” approach in clustering voters and building the issue dimensions. If our results did differ substantively from Drutman’s, we would be the first to question our analytic decisions.

DATA-FOR-STRATEGY: THE DEMOCRATS NEED BETTER, MORE OBJECTIVE DATA ANALYSIS, NOT MORE DATA

While on the subject of data analysis, the Democrats need to fully assess what went wrong with their 2016 analytics. Democrats, don’t tell us the analytics weren’t part of the problem when your own presidential candidate called them out (Here is a video of Hillary Clinton lashing out at the Democratic National Committee’s data program).

In the information age, data goes hand-in-hand with campaign strategy, operations, and tactics. Though collecting data-for-strategy is hard, the rules guiding such collection are simple. Data-for-strategy need to be reliable, accurate, and systematically related to organizational outcomes.

Effective strategy-building especially requires comprehensive, theory-based data collection. I will forgive anyone who rolls their eyes at the sound of “Balanced Scorecard” or “Lean Six Sigma.” Those are the Harvard MBA-bastardizations of the theoretically well-grounded work of W. Edwards Deming and others. But Democrats need to take Deming’s core lessons to heart. Measure what theory and experiences tells you to measure. Measure it often. Measure it well and in different ways. Determine what you can and cannot control. Act on what you learn. And then repeat the whole process.

It is not surprising, given data-for-strategy‘s business origins, that initially it was the Republicans, under the guidance of Reagan’s pollster Richard Wirthlin, that best exploited data for electoral purposes.

However, since the Bill Clinton presidency, the Democrats are arguably the dominant party in the employment of data analytics. The George W Bush 2004 presidential campaign may have pioneered the use of big data operations, but it was the 2008 and 2012 Obama campaigns that took it to its highest practical levels.

The problem for the Democrats has been that the Trump campaign (through Jared Kushner’s efforts) matched the Democrats in the utilization of big data but didn’t disregard other old school data collection efforts (surveys, focus groups, etc.). Hillary Clinton did (thanks largely to her big data apostle, Robbie Mook) and it contributed significantly to her defeats in Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania. Mook let the expense of a few five-digit-dollar-cost surveys compromise the success of a one-and-half billion dollar campaign.

Another problem with big data analytics (for both parties) is that it relies on kitchen-sink predictive models at the neglect of theory-based model-building. Such models, that include nearly every variable available (web usage and online purchasing databases are flush with variables — not necessarily useful ones, however), are prone to modeling random error and are susceptible to large predictive errors, especially when making predictions over long time horizons.

Good data is critical to strategy-building and diversity in its collection is critical. There are no shortcuts and big data without theory is little better than instinct. It may even be worse. Ask Robbie Mook.

More importantly, analytics like Drutman’s are too blunt and time-specific to provide information close to what is needed for effective strategy-building. It may be that the Democrats can afford to move more decisively in the progressive direction in 2018 and 2020. Levitz’ discussion on the economic rationale of Medicare-for-All, free public college tuition and guaranteed employment is far more useful in that effort than his interpretations of Drutman’s and others’ survey results.

Drutman’s conclusions (and by extension, Levitz’) describe well the 2016 election. Unfortunately, they provide little pertinent information to build the Democrats’ strategic plan for the 2018 or 2020 election.

About the author: Kent Kroeger is a writer and statistical consultant with over 30 -years experience measuring and analyzing public opinion for public and private sector clients. He also spent ten years working for the U.S. Department of Defense’s Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness and the Defense Intelligence Agency. He holds a B.S. degree in Journalism/Political Science from The University of Iowa, and an M.A. in Quantitative Methods from Columbia University (New York, NY). He lives in Ewing, New Jersey with his wife and son.

A BRIEF NOTE ON YOUGOV’s SURVEY METHODOLOGY

YouGov’s “The View of the Electorate (VOTER) Survey” is an internet-administered survey of 8,000 adults (age 18+) completed between November 29 and December 29, 2016. YouGov uses a non-probability sample frame for drawing samples and excludes U.S. adults without reliable internet access. According to Pew Research, 13 percent of U.S. adults lack internet access as of late 2016. It was also found that U.S. adults lacking internet access are more likely to be older, less educated and living in rural areas compared to other U.S. adults. It is a fair assumption that they are more likely to be Republican and/or politically conservative.

To mitigate any sampling and nonresponse bias, YouGov employs an elaborate sampling and weighting methodology. A more complete description of the YouGov panel methodology is available here. It should also be noted that the YouGov internet panel has been deemed by Pew Research as more accurate and reliable than other internet-based surveys and last year fivethirtyeight.com gave the YouGov presidential polls a grade of ‘B,’ noting that its polls tended to have a mean-inverted bias of 1.6 percent in favor of Democrats. That is a relatively small bias.